INTERVIEW: MENAHEM GOLAN

By Oren Shai • Aug 20th, 2008

Right off the bat I must admit that I am biased. I admire this man. Menahem Golan is approaching his 80th year and showing no sign of stopping. His latest film came out in Israel’s theaters in July, he is trying to get a large international production off the ground, has just directed a stage show, and has various other projects floating around. The man is a purist; his dedication and love for film is undeniable and scarce in today’s generation of filmmakers. Jerry Lewis coined the term, “The Total Filmmaker”; Golan fits the bill.

Golan is a pillar of the Israeli film industry; take him out of the equation and its history will collapse. From the 1960’s to the 1980’s, he and his cousin, Yoram Globus, were involved in the creation of every genre and trend in the industry as well as responsible for most of the Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations garnered by Israeli films.

In 1979, Golan and Globus bought The Cannon Group and for the next 10 years they produced a slew of action films, dance musicals, teen comedies, etc. By1986 they were producing more films per year then all the Hollywood studios put together. Golan often said he would feel like a criminal making one $30 million dollar film rather than 30 films for $1 million each. The quality of their product was far from consistent but often extremely popular. But they overextended themselves by taking over theater chain after theater chain in Europe, and eventually Thorn EMI in England. At the end of 1986 their financial problems were piling up and by the end of the decade they were going bankrupt.

Cannon’s importance and relevance to the American film industry has been downplayed. Their ultimate demise allowed for them to be forgotten. Their Hollywood misadventures are legendary, and it is easy to be critical since many people claim to have been hurt by Cannon. Producing films is no reason to mistreat anyone, but in reality that is the case with an endless line of film producers in a town that was built on backstabbing. While criticism is legitimate, their achievements should be looked upon as well. Shelly Winters, who worked with Golan many times, once compared the cousins to the old Hollywood moguls: “They’re like the old-style bastards. We hated them, but they loved films. They created great stars and great films.”

Cannon reached groundbreaking agreements with the Hollywood unions that made it possible for the independents to grow. They were amongst the first to utilize the home-video market and they created stars and genres that have an impact on Hollywood to this day (clearly the successful STEP-UP series is the evolution of BREAKIN’).

In the decade that preceded Miramax, before independent cinema was “hip”, before it became a genre rather then a reality, Golan pushed Cannon to take chances on many directors who had a hard time getting the major studios to produce their movies. A partial list includes John Cassavetes, Robert Altman, Andrei Konchalovski, Franco Zeffirelli, Jean Luc Godard, Lina Wertmüller, Norman Mailer and Fons Rademakers – whose Cannon-produced THE ASSAULT (1986) won an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Roger Ebert said in 1987: “No other production organization in the world today has taken more chances with serious, marginal films than Cannon.”

In his diary from the 1986 Cannes Film Festival, “Two Weeks in the Midday Sun”, Ebert writes that for him, Golan was the hero of the festival. On May 7th, 1986, Variety printed this joke from Cannes:

“When Steven Spielberg got to the pearly gates, he asked St. Peter if Menahem Golan was inside. Assured Golan had not yet been called, Spielberg went in. On the heavenly throne, however, he spots an individual before a bank of phones barking commands, “Sign Dustin Hoffman, get me Coppola, buy Thorn EMI, sign Joan Collins for ‘Regine’!” Spielberg walks out in a huff, “I thought you said Menahem Golan wasn’t here” he blurts, “That’s not Menahem” replies St. Peter. That’s God. He just thinks that he’s Menahem”.

Golan grew up in Tiberius, a city located in northern Israel, on the Western shore of the Sea of Galilee. He starts the interview by talking about his love for film as a child.

Menahem Golan: There was a film theater in Tiberius that screened 3 or 4 films a week and I wanted to see them all. I didn’t have any money so the projectionist agreed that I turn the subtitles, he thought I understood English. Back then subtitles were not attached to the negative, there was another wheel that had to be turned simultaneously with the dialog. But my English wasn’t very good and I would stare at the film and forget to turn the titles. I still remember the shouts from the theater: “Menahem, subtitles!”

We had an attractive Home Economics teacher in school, she was about 40. She sat on her desk on Fridays and lectured us. We would take a steel rod, attach a mirror to the edge and push it forward, placing bets on the color of her underwear. One day she complained and our teacher punished us - Chaplin’s THE GREAT DICTATOR was coming out that Saturday night and we were forbidden to go to the cinema for a whole week. Of course I went to see it anyway. I didn’t realize the teacher was smarter then me and hid in the back row and a day later, in class, he asked me where I was last night, I said I was home and then I got the strongest slap of my life. I was expelled from school and it took my dad two weeks to convince the teacher to take me back. But I got to see THE GREAT DICTATOR!

Oren Shai: You got into theater before film. How did that come about?

MG: Around 1949-1950, after I was discharged from the Israeli army, my father gave me $10 and with that I left Israel on a ship. I reached Genoa, Italy and from there took a train to Paris, where I had friends. In the train, I held onto my money, not spending it on food even though I was hungry as a dog. In front of me sat a French nun, I will never forget her, she asked me, “Why aren’t you eating?” She taught me that a hungry man should put some white sugar on his tongue, because it depresses the hunger. She gave me a bag of sugar. I got off the train in Paris, starving, opened up the bag and there, on top of the sugar, laid 10,000 Francs. She gave me a gift and I lived in Paris off that money for a month.

I continued to London where I got a scholarship at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts (LAMDA). I started directing students and eventually they sent me to study direction at the Old Vic Theater. I spent 3 years in England.

When I returned to Israel I started working for various theaters where I directed adaptations of American musicals.

OS: And after a few years you went to film school.

MG: When I was about 30-32, I moved my family to New York so I could study film. I took classes at Columbia University and New York City College. I did that for 3 years while working at the Israeli consulate.

Then I heard that Roger Corman was traveling to Europe to film THE YOUNG RACERS (1963). I wrote him a letter and asked to join the production, I didn’t ask for any money. He responded that if I can be at the Palace Hotel in Monte Carlo on June 6th, I could be his driver.

On the first weekend Roger got the crew together and said “tomorrow we have to shoot the winner of the race receiving his flower wreath.” This is Saturday evening and we are shooting on Sunday, and there is no prop-master on set. He asked who could find a wreath and I volunteered. But how do you get one at 10pm in Monte Carlo?

I found a flower shop that was closed. I looked inside and all of a sudden a police car pulls over and French policemen jump me as if I was going to rob it. One of them spoke English and I explained the situation to him.

They ended up being pretty nice and drove me to the mountains, where the owner lived. We drove back to his shop and worked all night, preparing the wreath. At 7am I was on set, ready to go. Roger Corman called the whole crew and said: “Look at this guy, he is the first producer I’ve met who will be better then me.” And I became one of his assistants.

OS: What did you learn from Roger Corman?

MG: I learned that nothing could stand against the will of the producer. If the producer can’t work according to the plan and schedule he created, he will fail. Working with Corman was a production school; he is a man of great cinematic stature.

OS: Francis Ford Coppola was the soundman on THE YOUNG RACERS.

MG: I once asked him, “Do you know anything about sound?” and he answered, “No, I’m looking at the manual.”

I told Corman about EL DORADO, a script I wrote with Yigal Mosenzon during my last year in the US. Theodor Herzl said that if we had a Jewish cop, a Jewish thief and a Jewish whore, we would have a country. So I was going to make a film about a cop, a thief and a whore. That was the story of EL DORADO.

I said, “Maybe you can help me? I need money to make this film.” He asked how much and I threw a number, $30,000. “What will I get from it?” “You’ll get the whole world, all I want is the rights in Israel.” Francis Ford Coppola sat next to us and told Corman, “Are you crazy? I will make you an American film!” Corman said, “but he came with a story and a script.” Coppola said he would bring Corman a script in the morning. Our rooms were right next each other and all night I could hear him typing on his machine. The shoot continued to Liverpool and Coppola crossed the channel to Ireland and got to make his first film, DEMENTIA 13.

After the shoot I returned to Israel and approached Mordechai Navon, the first producer in Israel, he agreed to make EL DORADO if I worked for free and took a percentage of the gross. It was my first film and it brought 600,000 viewers to the theaters.

Since then I made movie after movie in Israel. When SALLAH (1964) came around, my cousin, Yoram Globus, joined me and we started our production company, ‘Noah’, named after my father. By 1979 we had made 49 films.

OS: SALLAH was the first film you produced for another director.

MG: Yes, the reason was that Efraim Kishon, the writer, wanted to direct it. But I liked the script and agreed to produce with him as director. My contribution was bringing the cinematographer, Floyd Crosby (HIGH NOON, THE YOUNG RACERS), his wife (who was the continuity girl) and the rest of the crew, all who had worked on my previous films.

SALLAH was the first film from Israel to be nominated for an Academy Award.

OS: In 1968, TEVYA AND HIS SEVEN DAUGHTERS, which you directed, was in the official competition at Cannes. That was the year of the May crisis and the festival closed down in support of the strikes and student demonstrations.

MG: We were in the competition next to big films like Sergei Bondarchuk’s WAR AND PEACE and Milos Forman’s THE FIREMAN’S BALL. There was a meeting one morning, all the directors whose films were in the competition participated. I felt pretty small next to Forman and Bondarchuk. In this meeting we decided to shut down the festival. I had to vote for it because they wanted to, as a gesture of support for the students.

OS: You weren’t really for closing it down?

MG: No, I wanted my film to screen! The strike broke on the night of our screening; Godard ripped the screen and yelled to close the festival. But we did manage to screen the film at midnight. Then there is the story of WHAT’S GOOD FOR THE GOOSE.

OS: Do tell.

MG: We went back to the hotel when our screening was over and in the elevator someone overheard my wife and me speak Hebrew. It was a group of British people; one of them asked, “Are you connected to this movie?” He presented himself as Tony Tenser, “I’m a producer from England.” I told him what I always say, “Let’s do a movie together.” He asked, “Do you have a story?” “Of course I have a story!” He told me to come up to his suite, we’ll have a drink and I will tell him my story.

During that drink I invented a story about a bank clerk who travels to a convention in Brighton, picks up an 18-year-old hitchhiker and starts living as if he was 18 himself. Tenser thought it would be a great idea for Norman Wisdom, who was a huge star in England. If we get Norman Wisdom, we can make the film.

I get up early the next morning and there are no trains, no buses, everything is on strike. I hail a taxi and ride to Milan and from there take a train to London. Somehow I tracked down Norman Wisdom’s address through the British actors union. I go to his villa in central London and his maid comes out, asking if he is expecting me, I say, “Tell him there’s a director here from the Cannes film festival.” He comes down wearing a silk robe, I tell him my story and he likes it. So I asked if he could write on a piece of paper that he agrees to do the film and he did, if he gets his salary.

I got back to Cannes a day later and everything was still closed. I looked for Tony Tenser and found him on the beach, “I called you yesterday, where have you been?” he asked me. I told him I went to London, “Impossible” he says.

“I have a note here for you.”

So that’s how that film got made, it was an international hit.

OS: Which films influenced you the most?

MG: Italian Neo-Realism had a great influence on me.

OS: Any specific ones?

MG: Pietro Germi’s SEDUCED AND ABANDONED, Vittorio De Sica’s TWO WOMEN and MIRACLE IN MILAN. These films were inspired by the poetics of the people. I come out of the assumption that a filmmaker, a film director, is like a storyteller who sits in a market with his mandolin or guitar, singing about a better life, about princes and princesses, about kings and queens, an imaginary better world.

Spielberg’s E.T. also influenced me later. I think we live in a sad world, always searching for creatures in the universe that have some of us in them, the human brain. These things are all looking for happiness in another life, a better world. That is where my cinematic conscience is, I want to entertain people and offer them a better world, one they will see and think, “This is how I want my life to look.”

OS: You sold a few of your Israeli films to American distributors. FORTUNA (1966) was sold to Sam Arkoff (American International Pictures).

MG: We held a screening at his house and he said, “Look, it’s not a film for America. It’s too Jewish, but I’ll give you $10,000 as a donation.” I said I don’t want a donation, if it’s not good he shouldn’t buy it, so he ended up buying for $10,000, but I don’t think it was ever screened.

OS: KAZABLAN (1974) was sold to MGM.

MG: We invited their President of Distribution to the premiere in Israel and sat him in the theater next to the Israeli president. He was impressed by the film and said he would give us half a million dollars, an amount you didn’t even dream of back then, in order to make an English version. I had already shot the film in English as well, and he invited me to Los Angeles to re-edit it. It was a hit in a few countries.

[OS note: KAZABLAN was nominated for Golden Globes in both Best Foreign Film and Best Song categories].

OS: In 1975 you directed LEPKE in the US.

MG: The head of the ABC Theaters chain in California, a man named Plitt, rang me up when I was in Los Angeles, “I watched KAZABLAN yesterday and they gave me your number, but MGM won’t let my chain distribute it; they are going with my competitor. Can we talk?” I came to his office at Century City and he told me he was the biggest donor to Israel in Los Angeles. I spoke to everyone at MGM and eventually they agreed to give ABC the film.

I suggested to him, “If you really like this one, let’s make another film.” He asked if I had a story so I said I’ll have one tomorrow. I went to a bookstore and bought an encyclopedia of crime in America. I figured I should find something I know about - a Jewish criminal. I found Lepke Buchalter, who ran a Brooklyn company called ‘Murder Inc.’ He would kill anyone for money.

A day later I gave Plitt a synopsis I wrote and he questioned, “Do you really think there will be an audience for a film about the Jewish mafia?” I answered, “Why not? The Italians are making blockbusters.” He agreed to invest $300,000. I called Yoram and we got another $700,000 on loan from the bank. Tony Curtis starred as Lepke, and Warner bought it from us.

OS: But you had a lot of problems with the Hollywood unions.

MG: They held the film from being released for 2 years. The major studios had contracts with the unions, so on one hand we were signed with Warner and on the other we didn’t have union permits. We ended up paying a fine for it.

OS: Two films you produced for director Moshe Mizrachi, I LOVE YOU ROSA (1972) and THE HOUSE ON CHELOUCHE STREET (1973), were nominated for the Best Foreign Language Academy Award. In 1978 you were nominated for a film you directed, OPERATION THUNDERBOLT, and Mizrachi competed and won the award with a film he made in France, ROSA. How did you react to that?

MG: He is an excellent director. I was very proud of Mizrachi. OPERATION THUNDERBOLT was an action film, not an artistic film. The fact that we were amongst the 5 nominees, the 5 best foreign films in the world, next to directors like Bunuel, was enough.

OS: That was one of your 1978 successes; the other was LEMON POPSICLE, which was sold all over the world. After that, in 1979, you and Yoram bought The Cannon Group.

MG: Cannon was a New York based company that had one hit film, JOE, starring Peter Boyle, which was when they turned Cannon into a public company. They lost a lot of money throughout the years and had about 60 films they never sold outside the US. Yoram and I approached them with an offer to give us those films, mostly ‘tits and ass’ movies, and we would sell them for a %25 commission. In May we took them to Cannes and made $2 million out of sales to Germany alone! That left us with a half a million dollars commission and with that money we bought Cannon. We used their own films to buy them.

We moved to Los Angeles and started by producing THE HAPPY HOOKER GOES TO WASHINGTON and B-action pictures.

OS: Was there a need in the industry that you thought you could supply?

MG: The unions were very strong and the majors were tight with them. There were strikes that gave power to the independents because they were not dependent on the unions, they made films with young people who were all over Hollywood and couldn’t get jobs.

Cannon deserves credit for the biggest achievement with the Directors Guild of America. I was in New York, directing OVER THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE (1984) with Elliot Gould and Margaux Hemingway and the DGA tried to shut down my production. They formed a picket line of directors so my actors couldn’t get to the set. I agreed to negotiate with the heads of the guild, together with my lawyer, Sam Perlmutter. It was impossible that a film made by the majors for $50 Million would get the same union terms as a film made with a budget of $1 Million. It wasn’t fair. We invented a rule that any film made for under $3 Million gets a separate set of terms and salary requirements. We signed what became known as the “Cannon contract”. Later we got these contracts with the technician unions as well.

That’s how the independents developed, this contract allowed members of the unions to work on independent productions.

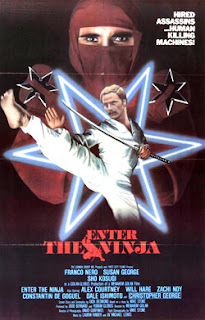

OS: You started the Ninja craze in 1982 with ENTER THE NINJA.

MG: It started when Chinese Karate films became popular. I looked for something new in Asian martial arts and found information about the Ninja culture in an encyclopedia. The Ninja were middle-class people in Japan - lawyers, government clerks, etc. It was a secret organization that helped the Feudal government. It actually preceded the Chinese Karate battles. They used very special methods, developing their sixth sense. That fascinated me and I said I could write story ideas out of it, so we made ENTER THE NINJA and AMERICAN NINJA later on. Many imitations followed.

OS: You discovered Michael Dudikoff in AMERICAN NINJA, but it was supposed to be Chuck Norris at first.

MG: Yes but by then he was too old for that part. Dudikoff was a handsome young martial-artist, we started using him in films as soon as he came to us.

OS: How did your relationship with Norris start?

MG: Chuck came to us with an idea for a film; it was after we made a few action pictures. He made a film with Orion before that. We signed him to a 7-year contract; it’s the first time this was done since classic Hollywood. 7-years at 2 pictures a year.

OS: What was your biggest hit with Norris?

MG: The MISSING IN ACTION series.

OS: In 1982 you produced DEATH WISH 2. You bought the rights from Dino De Laurentis, who produced the original.

MG: It wasn’t easy but he wasn’t in a good financial state and sold us the rights. We made 4 sequels.

OS: It also started a long-term relationship with director Michael Winner. You made THE WICKED LADY (1983) with him next.

MG: There was a dispute in Cannes that year. They appointed me as a judge in the festival and then, out of the blue, informed me that they had invited someone else instead of me. I sued them, and to settle it, they agreed to screen THE WICKED LADY in the competition. But it wasn’t worth much because the film wasn’t good.

OS: How did you get involved with Andrei Konchalovski? Cannon brought him to America and had a long-term production relationship with him.

MG: Konchalovski was introduced to me at Cannes. He told me a story about a soldier in Yugoslavia who returns home after WWI with shell shock, not able to have sex with his wife. I told him, “Go downstairs, get some coffee and start thinking this way: He is not a Yugoslavian soldier, he is an American soldier, the war is not WWI, it’s Vietnam, and make the story contemporary.” Ten minutes later he returned and with the revised idea, which became MARIA’S LOVERS.

OS: You also worked with J. Lee Thompson, who directed the original CAPE FEAR (1962) and THE GUNS OF NAVARONE (1961).

MG: We made one of the DEATH WISH sequels with him, and THE AMBASSADOR (1984) and KING SOLOMON’S MINES (1985). Here I have a story with Sharon Stone. I saw her as an extra on a TV show and called her, “Want to go to South Africa and shoot a film with Richard Chamberlain?” She agreed and we made that film and its sequel with her. After that Arnold Schwarzenegger saw her and cast her in TOTAL RECALL.

OS: Didn’t Schwarzenegger come to you early in his career?

MG: He came to meet me in Tel-Aviv when he was still a body builder, asking that I cast him in a film. I couldn’t believe that this muscleman, who spoke German, would ever make an American motion picture. He said, “Herr Golan, make a movie with me” and I responded, “Herr Schwarzenegger, go to America, don’t do anything for two years, learn English and change your name because Schwarzenegger is not a name for a movie star”.

A few years later I met him on some yacht in Cannes, surrounded by women, he called me out, “Herr Golan, look, I still hardly speak English, I didn’t change my name, and who’s the biggest star in the world?”

OS: Around 1982 you started buying film theaters in Europe. You made a lot of changes to theater standards: weren’t you the first to introduce the multiplex in Italy?

MG: We were the first ones in England too. We modernized the theaters and made them smaller. Before that, especially in London, there were big theaters that fitted 2000 or 3000 people and it was usually 3/4 empty. That type of theater didn’t attract audiences anymore and the smaller ones took its place. Film theaters started attracting viewers back after losing many in favor of TV.

But you can’t be a film producer and a theater owner; it’s a big financial mistake. You need to be physically involved with the theaters. That was ultimately the reason we fell; we overextended ourselves. You couldn’t control the theater chains as well as the productions. We owned most of the theaters in England and had large chains in France, Holland, Italy and Israel of course. We used junk bonds from Wall Street to buy them, a big mistake that hurt Cannon and caused Yoram and I to separate.

OS: What was the reaction in England in 1986 when you took over Thorn EMI and the Elstree Studios?

MG: It wasn’t easy for them to accept us. All of a sudden a couple of Israelis take over all of their theaters.

OS: Was it hard to deal with?

MG: No, they needed us.

OS: This photo on your wall, of you and Yoram with the Queen of England. What’s the story behind it?

MG: They sometimes have premieres at the palace for different benefits, so we donated ORDEAL BY INNOCENCE (1984), which was based on an Agatha Christie story.

I sat next to the Queen during the screening, it was forbidden to speak to her unless she spoke first. There are all these rules, I had to take off my watch so that there would be nothing that can scratch or hurt her. You go through a whole course before a screening with the Queen. In the middle of the film she asks me, “There were 4 deaths already, how many more are in the film?” I answer, “Two or three” and she says, “That’s a lot of casualties. You are going to make a lot of money.”

OS: Cannon’s first big hit was BREAKIN’ in 1984.

MG: My youngest daughter, Yael, told me I had to come to Santa Monica and see what’s happening on the beach. She took me there and I saw groups of African Americans, dancing in a way people didn’t know. I said, “We need to write a script about it”. So I wrote the story and brought in a screenwriter, then I called Joel Silberg who directed a film in the Philippines for me. He directed BREAKIN’ with a cast who were mainly young people we got in Santa Monica.

We wanted MGM to distribute the film and screened it for them when it was finished. The management was there and they said it was a “black film”. Back then the African American community wasn’t a dominant force at the box-office.

I told MGM they had to give us another screening. We handed out tickets to kids on the streets and brought them in. Within 5 minutes of the film’s start, they were all dancing on the seats. So I asked MGM, “Well, what do you think of my movie now?” They told me, “It’s a good film for black people”. They planned to screen it on one screen in San Francisco, one in Chicago and one in Los Angeles. I said, “Do whatever you want”.

The distributor in the American system at the time, sent the films to the franchise owners and they decided how many copies they needed. Before they could say ‘Jack Robinson’, 1200 copies were ordered, which was a huge amount for a small film. It grossed $6.5 million on the first weekend and eventually got to $60 million. We made a lot of money and MGM signed a distribution contract with us.

Later we made another film with Joel, RAPPIN’, but it wasn’t very successful. We produced about 10 dance films.

OS: At what point did you start producing films straight-to-video?

MG: It started with the Ninja films and grew from there.

OS: Were you the first to release sequels directly to video?

MG: Yes, no one did that before us.

OS: You were known for selling your films for distribution at Cannes before a script was even written.

MG: We sold them using posters but we had to supply the investors with the films afterwards, otherwise they would have lost their trust in us.

Golan and Globus as the heads of Cannon

OS: In 1984 you produced LOVE STREAMS for John Cassavetes.

MG: Working with John was wonderful, very creative, an exceptional man. He was sick when we made LOVE STREAMS, it was all shot in his house. He edited the film and screened it for me. It was two hours long. I told him, “Listen, the movie is wonderful but a little boring at two hours. Take half an hour out.” He agreed, “Come next week, I’ll have a screening and do what you want.” He edited his films in New York so I flew over a week later and the film wasn’t two hours long, it was two and a half hours! I asked him, “John, didn’t you say you will cut it shorter?” and he replied, “That didn’t look shorter to you?” Eventually he cut it back down to two hours. We won the Golden Bear at Berlinale with it.

He called me when he was in the hospital and told me, “I have a great story to tell you.” I said, “Get out of bed, come over, we’ll start producing.” But he never got up from it.

OS: Even though the Action films were your main product, you managed to get a lot of artistic directors to work for Cannon.

MG: I admire great directors and like working with them, learning from them. I pushed for the artistic films and in order to finance them I also pushed for more action films. That’s what happened, the Action financed the Art.

OS: BARFLY (1987) was another one.

MG: Barbet Schroeder approached me with the Charles Bukowski book. I liked it and said we’ll make the movie in half a year. Barbet insisted, “No, we start now.” “But Barbet, we need to raise money, cast stars, it takes time.” He nods, “No, no, no, we start shooting in a month.” I explained we can’t and he took out a huge knife from his pocket and put it against his finger, “Yes or no? If you say yes, great. If you say no, I’m cutting off the finger.” It was crazy. I managed to convince him we need time. I was going to London that night and told him we can talk when I’m back in 3 days.

Around 2:00 am, at the London hotel, a guard woke me up and told me there’s a crazy guy outside, threatening to cut a finger off. I asked them to put him on the phone, “Barbet, what’s going on? Are you crazy? I’m coming back in two days, we’ll talk.” “When do we start?” “When do you want to start?” “We shoot in a month.” I said, “Ok, you got it, let the finger go.”

OS: Was Cannon unique in producing these type of films as an independent company?

MG: We were the only ones. The artists within the directors knew that our door was open to them because I’m there and they could talk to me. We often lost money on these films but we had a great selling method for the action films and we brought big stars who agreed to work for low salaries with these directors attached.

OS: In 1987 you produced KING LEAR for Godard.

MG: Godard called me from the bar of my hotel in Cannes, “You want to come down? I’d like to talk to you.” I went downstairs and he told me, “I have two projects, one of them is KING LEAR, but it’s not really about King Lear, it’s about a gangster. I need a million and a half.” I said, “Godard, with you I’ll film the phone directory.” We signed a contract on a napkin. He made a terrible film.

OS: What was the experience of working with him like?

MG: Godard is an individualist. On the one hand he’s a genius and on the other a manipulator. He would call me in Los Angeles, recorded the conversations, and played them in the opening of KING LEAR. He didn’t have enough respect for the producer, shot the film in his back yard and pocketed money. I don’t have a lot of appreciation for him. Outside of the glow I get as a producer for having worked with him, I really couldn’t stand it.

OS: Was there a difference in your work as producer with a director on an artistic film and an action film?

MG: For me a director is a director, he dictates the piece, creates it and I need to help him. The producer brings together all the elements that make it possible for the director to make the film - develop the script, hire the actors, hire the director and then work together with him. The director is the architect and the producer is the engineer.

OS: But there were times you looked at footage shot and deemed it wasn’t good enough.

MG: Yes, that happened a few times and I jumped in and took over as director. In ENTER THE NINJA for example, we sent a crew to film it in the Philippines with an American director and when I saw the dailies I got really scared. It wasn’t good at all. We shut the production down and I flew from Los Angeles to Manila and took over.

OS: One of the most famous films you are known for directing is THE DELTA FORCE (1986). It was sort of a remake of OPERATION THUNDERBOLT.

MG: Not exactly a remake, but of the same genre. I liked using real political stories, not to send a message but as a suspense film with human action. There was a period when international terrorists abducted airplanes, and that formed the basis of a fascinating script. It was very helpful that I made OPERATION THUNDERBOLT before.

OS: THE DELTA FORCE features the last performance of Lee Marvin.

MG: Lee Marvin was an amazing actor and an amazing personality. He came to Israel to shoot the film. He loved the camera and sat next to it from morning until night. He would buy beers for the whole crew, was a really good and smart person.

[Our conversation is interrupted by a 15-minute phone call. A different Golan is revealed to me - The Producer. One I haven’t seen throughout the interview. The call was placed from Australia and while I couldn’t make out the details, Golan was explaining exactly what would work in a low-budget action film and every word made sense. He was energetic, decisive and sure of himself; he thrives on this type of action. At the end of his conversation he obliged me with some details.]

MG: We have an Australian actor named Tony White who we want to develop a film for. He wants to be the new Van Damme. I sent them a script I’ve written called STONE ROGERS. They are not sure about it yet. They like the character though. I have to think of a couple of Hollywood actors for the part of the ‘heavy’.

The story is about an electronics-manufacturing factory that the US builds in Thailand to compete with cheap labor from Japan and China. The Japanese want to hurt the Americans without going on an all-out war so they send a Ninja to kill the American engineers one by one. When the police in Thailand can’t contain the problem, they send two officers, a guy and a girl, to New York, in order to find someone who will fight the Ninja – sort of an American Ninja. They find this guy, who is Australian but can also be an American. He teaches the way of the Ninja at the NYPD. They enlist him and his commander and the four travel to Thailand. In the meantime, the bad guy, I call him the “Sho Kosugi”, starts a school for Ninjas in Thailand in order to attack the American factories. The NY officer has to eliminate this Sho Kosugi. He works alone and eventually he wins.

OS: You still write scripts? What is your process like?

MG: I just find an idea and write it.

OS: Any preferred time of writing?

MG: Especially on planes, but also at home in the evenings.

OS: And the producer wanted a star now on the phone?

MG: They wanted Van Damme to do a cameo but those things don’t work. They wanted either him or Chuck Norris so it would be easy to sell it but Chuck doesn’t act much anymore and Van Damme would want too much money. I’ll suggest a few names for the ‘heavy’.

OS: You discovered Van Damme.

MG: One evening my wife, Rachel, and I went to a French restaurant in Los Angeles. Our waiter was Van Damme, this good-looking French guy. We ordered turtle soup and he approached us, holding a bowl in each hand. He asked me, “Monsieur Golan?” I answered, “Oui” and he sent his leg kicking above my head, without moving the soup bowls! I asked him to do it again, he did, and I said, “What are you doing tomorrow morning? Come to my office”.

OS: Was he the biggest star Cannon created?

MG: Yes. BLOODSPORT, CYBORG and KICKBOXER made outstanding profits. But then Universal offered him a contract for millions of dollars and we didn’t want to pay that sum so we lost him.

OS: In 1986 you made COBRA with Sylvester Stallone.

MG: OVER THE TOP was shot first. It was based on a script about arm-wrestling. I bought it because I knew I could get a big star. I called Stallone’s lawyer and told him I had a great script I wanted him to read. He advised me to forget it because Stallone was getting $6 Million per film, so I told him, “I don’t want to pay him 6, I want to pay him 10.” Within the week I had a meeting and signed a contract.

We made COBRA immediately after, it made $125 Million.

[OS Note: Next to countless certificates of award wins or nominations on Golan’s wall, there is one from the International Armwrestling Council, inscribed, “IN APPRECIATION FOR YOUR VALUED SUPPORT FOR THE SPORT OF ARMWRESTLING.”]

OS: Cannon also produced some big flops in 1986 (MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE, SUPERMAN 4: THE QUEST FOR PEACE).

MG: At the end of the year we were always in profit. The theater chains caused us to lose money, not the films. We made 49 films in 1986, which was a mistake, but we still ended up with profits from them.

OS: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) started an investigation against Cannon in 1986 as well.

MG: In a public company you have to estimate the income for 7 years in advance and there were over-estimations here done by accountants. I wasn’t really involved in it, I worked on the productions.

The real decline came about because of the junk bonds, there was very high interest on them.

The Cannon logo embedded on their stock

OS: But Cannon wasn’t the only Independent in decline. In 1987 almost every independent company lost money.

MG: A lot of it was because of the Credit Lyonnais bank. They financed all the independents and stopped giving large credit to them because of losses.

OS: When did you leave Cannon?

MG: In 1990. I started the 21st Century Corporation but I didn’t have enough money or credit with the banks and didn’t have someone like Yoram next to me. He gets the full credit for taking care of the financial side.

OS: When you left Cannon, instead of taking financial compensation, you opted to take film options with you to the 21st Century Corporation.

MG: The intention was to take with me what I believed to be the most profitable film in history, SPIDER-MAN. I bought the rights to SPIDER-MAN from Marvel Comics when I was the head of Cannon. I even remember the sum, it cost $400,000. I held the rights for 7 years but wasn’t able to raise the budget of $50 Million. We developed screenplays but never got to make it. I ended up selling the rights to Carolco Pictures and they sold it onwards. Eventually Columbia got in the picture and we were left out.

I initiated making this film and CAPTAIN AMERICA when nobody wanted to touch comic book films. They made fun of me and I said “You’ll see, it will come back,” and it did, big time.

I tried to get some films off the ground at the 21st Century Corporation but I suffered great losses with one production, BULLSEYE! (1990), a film starring Roger Moore and Michael Caine, directed by Michael Winner. It was a comedy that wasn’t comedic. CAPTAIN AMERICA was a flop; PHANTOM OF THE OPERA was a flop…

[OS Note: Check out promotional material for Cannon's SPIDER-MAN, as well as other great Cannon posters and information, at www.cannonfilms.co.uk]

OS: When did you return to Israel?

MG: In 1992.

OS: And then you found yourself a new niche as a director.

MG: Yes, I received the Theater Award in Israel for my production of SOUND OF MUSIC.

OS: And you directed many Action films in Europe throughout the 1990’s.

MG: I came from a world of action cinema. I was sought after.

OS: What do you think of cinema nowadays?

MG: I am not a big fan of all the blockbusters they make in the US, they are far from the spirit I would like to see in movies. American cinema today is bigger, wider and costlier but it doesn’t supply me with the excitement I got from the Italian cinema for example. There are always exceptions but I’m more in tone with European cinema.

The Israeli film industry in my opinion has taken a big step forward, thanks to young filmmakers who are getting a chance to showcase their talents. They create cinema with great excitement. I hope it will continue to grow this way and I take the right to say that I laid a large portion of the basis for it.

OS: And what’s next for you?

MG: I am about to direct a film based on Aharon Appelfeld, “Badenheim”, it’s a great literary piece. I have been trying to raise the money for the past 4 years, around $15 million. It’s in the final stages and I’m hoping to get to shoot it in October.

My latest film, MARRIAGE LICENSE, starts playing in Israel on July 27th.

OS: You still have an amazing drive.

MG: I have love for cinema, that’s it. Somebody else has a hobby, I don’t have a hobby.

I make films, love them, sometimes I also do an excellent job. I don’t consider myself an Ingmar Bergman, I don’t make ‘message’ films. I make them for the audience in the theater who doesn’t get bored, laughs at a comedy, cries at a tragedy, with a lot of emotion. I’m hoping that there’s still a future.

没有评论:

发表评论